Courts & Justice in Tudor England

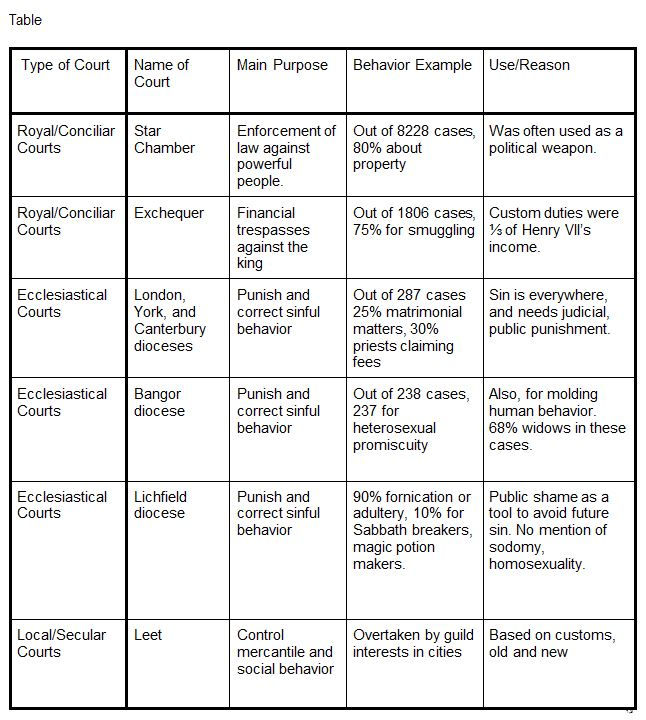

The common law legal landscape in 16th century England was a patchwork of courts and traditions where participants received different treatment based on their social status, location and even the year. The courts were not unified into a single, hierarchical system, and were often sorted by types of crimes, with each court developing its own unique expertise or specialty. The legal traditions of each court were different. The Tudor legal system relied on prior rulings and decisions, case law, and customs dating to Norman, Anglo-Saxon, and Roman times and also incorporating local legal traditions. This heavily fractured, very specialized and old legal system led many to despair at the sheer size of the legal structure and the judicial precedent with which they had to grapple. The handling of different crimes by different courts naturally led to social stratification as some courts dealt with crimes the average laborer would never be able to commit. The courts can be sorted into three rough groups: the King’s courts, which primarily handled political and financial crimes, reflecting royal interests; the Church courts, which sought social control and to mold human behavior, focusing on punishing sin and immoral behavior; and, the local courts, which handled secular, local problems. Please see the table below for more information.

A seemingly small, but profoundly important, contextual distinction in legal philosophy between the Tudor period and ours is the origin of justice. This question, of “Where does justice/sovereignty come from?” consumed European cultures in the centuries between our two periods. In our modern legal paradigm, justice and sovereignty move from the bottom up. Sovereignty lies in the citizen, who elect representatives who then vote on and confirm judges. Thus, the modern judicial system’s authority stems from the people, who have indirectly elected and given power to their judiciary. The Tudor period, in opposition to ours, saw justice and sovereignty moving from the top down. All power and authority sprang from the divine, who worked through an anointed monarch. This monarch spread this authority downward through the nobility and upper-class through chains of fealty, sponsorship, and ties both financial and familial. Tudor legal authorities could view their authority as divine in origin, and challenging this was tantamount to heretical treason, upsetting the Great Chain of Being. Justice unquestionably came down from the divine, where else could it come from for a Tudor, and the common man had little agency.

Local courts, especially the small rural ones that would be held at a manor home like Agecroft, were places where citizens attempted to resolve problems that affected them locally. These courts, like most Tudor courts, were places where the rich could expect preferential treatment. Nobles, gentry, rich yeomen and shopkeepers dominated the manor courts. Town mayors swore oath upon assuming office to “do every man ryght, as wel to the poor as to the riche.””iii But notice, the oath is not to “treat every man fairly” but to “do every man ryght,” expressing contemporary ideas about the role of the legal system and local leaders: they were to maintain law and order without showing undue favor to the rich or neglect the poor.The general issues brought before a local manor court was ones of public nuisance. Breaching the King’s peace, theft, cutting timber without a license, failing to maintain fences, and eavesdropping were all common complaints. The manor courts existed as a “final resort” used by the community against an offender who had already been chastised with less formal measures. A conversation with an employer or priest, social shunning, or binding over would all be attempted before bringing the issue before a court. Once indicted and brought before a court, an offender would face a judicial system largely made up of local well-to-do volunteers.If convicted, a prisoner would face a punishment explicitly intended to embarrass him and terrify the public. One of the most common forms of punishment was the pillory. If pilloried, a convict would be paraded to the instrument through a main thoroughfare accompanied by music. The psychological effect of this type of punishment, carried out in front of the only people a prisoner might know, drove some to suicide. Another type of punishment, carried out against low-class women and gossips, was the scold’s bridle. This iron headgear, with a piece of metal that extending into the mouth to pierce the tongue if it moved, was a terrifying public deterrent that still allowed the punished to work.

For the common man, local Tudor justice was an often terrifying extension of royal power, local authority, and the natural order. For the locally powerful, the justice system was a means of ensuring social order, protecting financial interests, and a political battlefront. This system, throughout much of England, based itself in rural manor homes like Agecroft Hall.

i Barnes, Thomas G. "Star Chamber: Litigants and Their Counsel, 1596-1641." Legal Records and The Historian, July 3, 1974, 7-28.; Guth, DeLloyd J. "Enforcing Late-Medieval Law: Patterns in Litigation during Henry VII's Reign." Legal Records and The Historian, July 3, 1974, 80-96.

ii Great Chain of Being. Digital image. Wikipedia. Accessed September 7, 2018 https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Great_Chain_of_Being_2.png

iii Carrel, Helen. "The Ideology of Punishment in Late Medieval English Towns." Social History 34, no. 3 (August 2009): 301-20. Accessed April 07, 2018. doi:10.1080/03071020902981626.

iv Pillory. Digital image. TeachPrivacy. Accessed September 7, 2018 https://teachprivacy.com/privacy-pillory-security-rack-enforcement-toolkit/; Scold’s Bridle. Digital image. This Bug’s Life. Accessed September 7, 2018 https://thisbugslife.com/2018/01/25/scolds-bridle-crikey/